Flag of the Eʋe Speaking People.

he Proto-Eʋe Speaking People, or the «People from the Great Valley» (of the Nile River).

- the use of the same Language (an old variant of Gbè named as Proto-Gbè in Linguistics, see Capo 1988 & 1991 cited in the References);

- the sharing of the same cosmogonic and spiritual Values that rely on the permanent and Triadic Equilibrium in the whole Divine Creation (see Folikpo 2017 cited in the References);

- the mastering of certain economic activities such as the extraction and the transformation of Iron, of Cupper, of Silver, etc. (see the video further about Gunu Dudji near Dogbo)

- the great importance given to the collective Memory through Orality over the generations (see for example Avogbedor 1985 cited in the References).

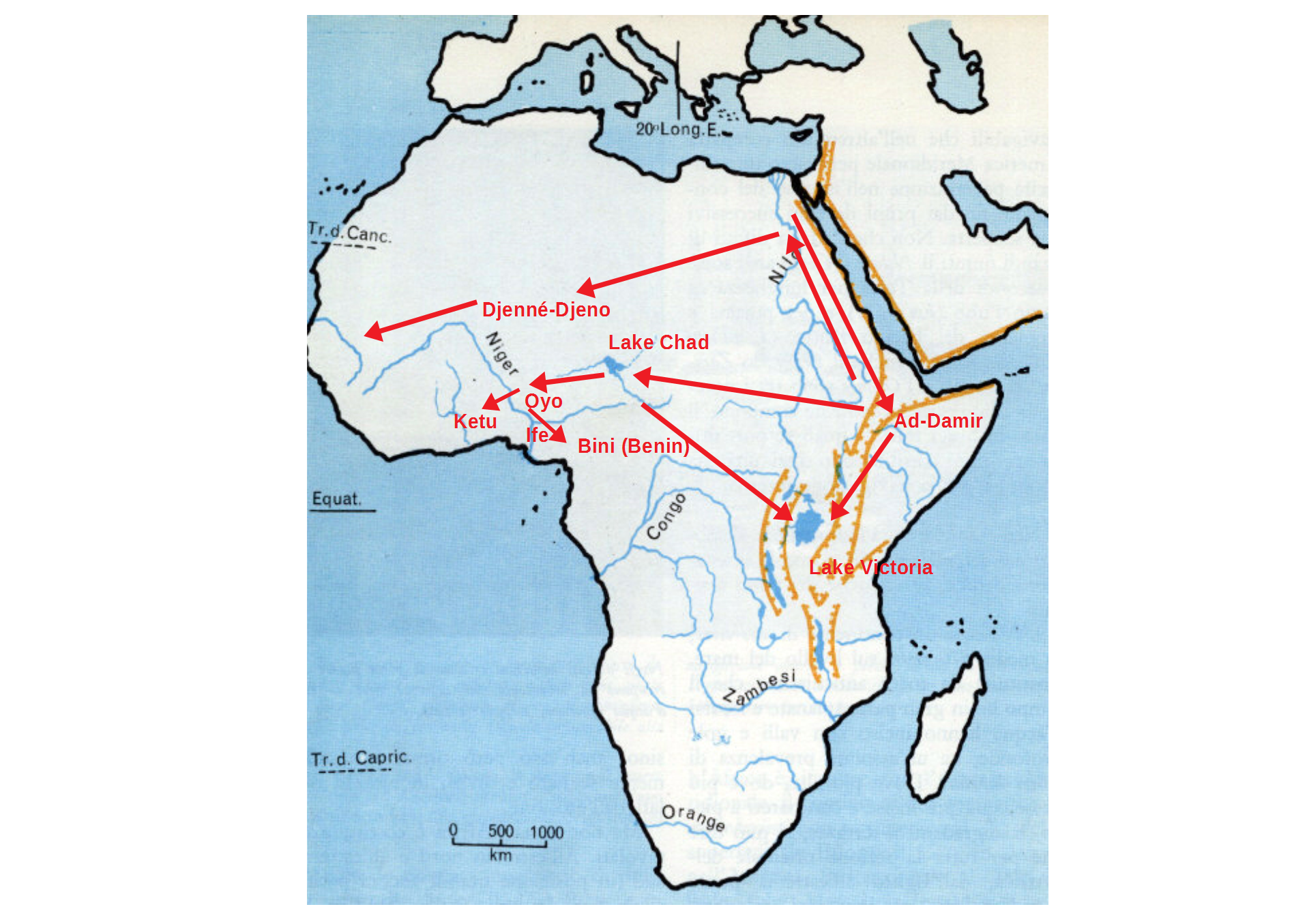

Map describing the Migration waves in ancient Africa from the Nile Valley to South-East Africa and to West Africa. (Map reproduced from illustrations of Gerhard Kubik and Paul Klaus Wachsmann)

Illustration of the stellar constellation of Sirius according to the description done

by Jakob Spieth and according to the Oral Traditions among the Eʋe Speaking People.

he Proto-Eʋe Speaking People in the ancient multi-ethnic Meroitic and Kushitic Kingdoms.

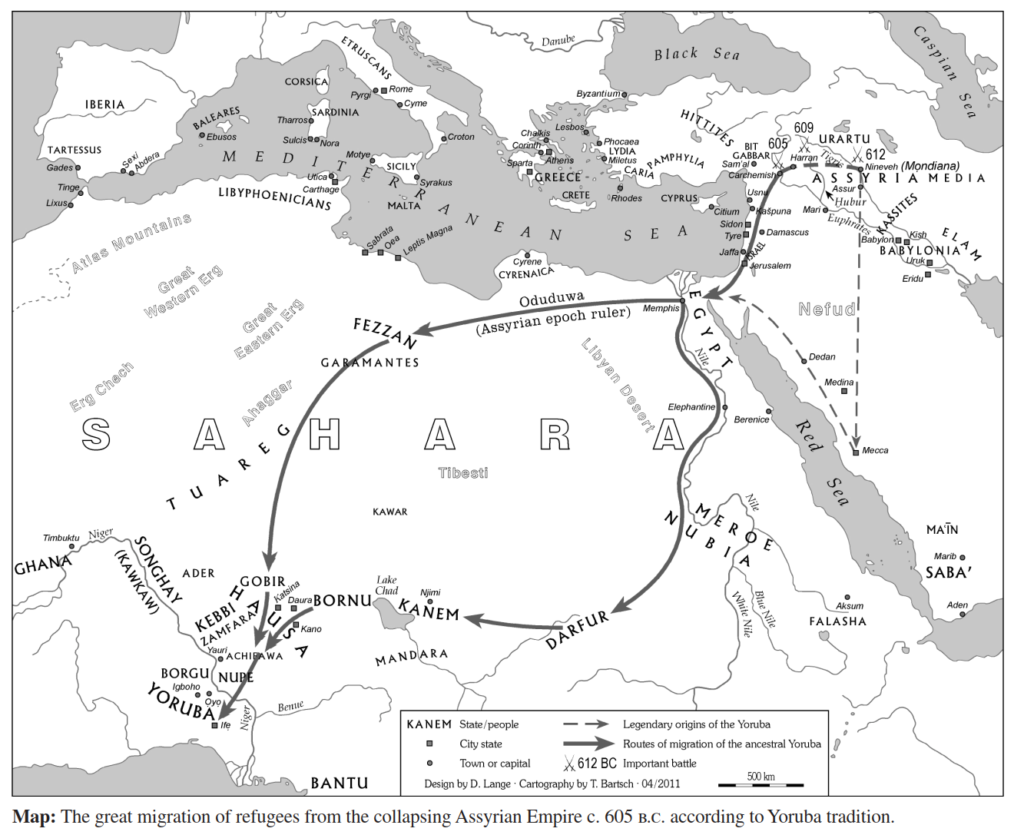

Oral Traditions among the Eʋe Speaking People and works done by the italian Anthropologist and catholic Priest Roberto Pazzi (see Pazzi 1979 cited in the References) mention that the ancient town known as Ada-Dam (that is Ad-Damir) was a very important station during their Migration southwards and westwards. Ad-Damir was an ancient and multi-ethnic town in the Kingdom of Meroë (see map below) that played a major role over centuries, as the archeological findings testify it till nowaday (see the map and the image below).

Ancient settlements of the Proto-Eʋe Speaking People in the area of Ad-Damir in actual Sudan, according to various works in the fields of Archeology, of Areal-Linguistics and according to the Oral Tradition of the Eʋe Speaking People.

(Credit Map & Photo: DPA Themendienst / Philipp Laage)

T

he Eʋe Speaking People in the ancient multi-ethnic Kingdoms of Bini (Benin), Ɔyɔ (Oyo) and Ilɛ-Ifɛ (Ile-Ife).

The legendary migration routes (shown by dotted arrows) and the really possible migration routes (shown by continued arrows) of the Yoruba Speaking People together with other social groups in the ancient times preceding the christian era. (Copyright Dierk Lange)

Opa Oranyan at Ilɛ-Ifɛ.

T

he Migration westwards of the Adja and Eʋe subgroups: Transit over Keto (Ketu) and the Foundation of the Tado Kingdom.

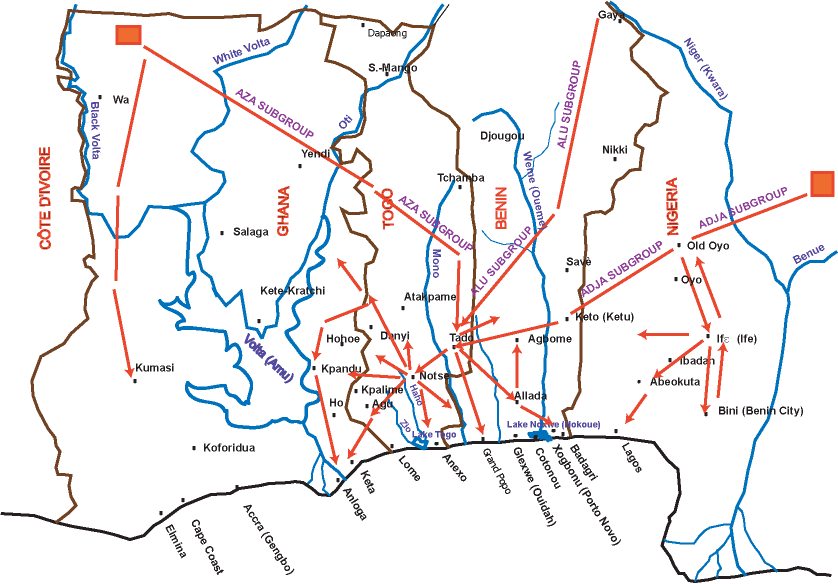

Map showing the major Migrations that lead to the Foundation of the Tado Kingdom, to the Foundation of the Ŋɔtsie Kingdom and to the «Breakout» of the Eʋe Clans from Ŋɔtsie (Notse). (Copyright: PYRAMID OF YEƲE)

The Power and the Glory of the Kingdom of Tado began to decline around the end of the 15th Century A.D. when it got involved in repeated wars against the Kingdom of Ɔyɔ (Oyo) and against the Kingdom of Bini (Benin) who had the full political control over the City of Gbagle (or Badagry, in the actual Federal Republic of Nigeria close to the border with the Republic of Benin) and who were trying to extend their influence to Keto/Ketu from where a part of the people of Tado migrated some generations earlier. The political problems got worse in Tado with internal conflicts among members of the royal Families about the line of succession to the throne. One of the consequences of these internal conflicts was the departure of a clan known as “Agasuvi-Clan” who went to found another Kingdom at Allada (in the actual Republic of Benin) that evolved later to the Foundation of the famous Kingdom of Agbome (Abomey). Other clans who were in majority from the Eʋe the Speaking People left Tado by the same time and moved southwards to settle down in some localities like Kóme (or Come, in the actual Republic of Benin), like Tɔkpli (or Tokpli, not so far from the Mɔnɔ-River) or like Tɔgodo (known today as Togoville on the banks of Lake Togo). The worst economic and social Factor in this chaotic historical context was the introduction of the awful Atlantic Slave Trade by the European Slave Traders who had brought all these Kingdoms to downfall. By the beginning of the 16th Century A.D. the Kingdom of Tado was no more so powerful, and other localities like Ŋɔtsie (Notse) started to develop more political influence.

T

he Migration of the Subgroup of the Eʋe Speaking People westwards and the Foundation of Ŋɔtsie (Notse).

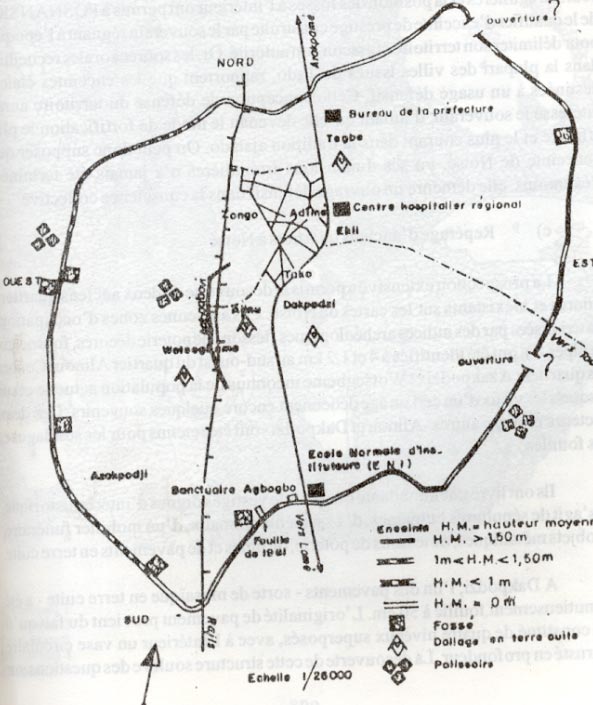

The frequent fratricide and weakening wars between the Kingdom of Ɔyɔ and the Kingdom of Tado by the beginning of the 16th Century A.D. and the impact of the growing Atlantic Slave Trade on these Kingdoms have brought the people of Ŋɔtsie to fear for their Security. They started to set up gradually their own Security Policy as well as their own local administrative Policy without expecting any empowerment coming from Tado as before. The massive immigration of the Akwamu people towards the banks of the Lake Volta by the beginning of the 17th Century A.D. (see for example Wilks 1975 cited in the References) has increased the fear of the people at Ŋɔtsie for their Security and for their political Freedom. The first attempts of the Akwamu people to create tributary relationships with the social groups living on the banks of the Lake Volta in an environment where the Atlantic Slave Trade was increasing have brought the people of Ŋɔtsie to transform their town in a City-State having all functional political and economic Structures and to protect this as well as its Inhabitants by building a very tick Wall as Fortifications all around, as shown by the Image and the Drawing below:

Restored Ruins of the Wall known as «Agbògbò».

(Credit: Togo Tourisme)

Map of the defensive Fortifications known as Agbogbome around the City-State of Ŋɔtsie (Notse).

(Credits: Angèle D. Aguigah / Nicoué L. Gayibor)

The decision to transform the town of Ŋɔtsie (Notsie) into a City-State having all these functional Structures and the decision to build these protective Fortifications around the City-State were not the sole initiative of King Agɔ-Kɔli (who was the third or fourth King), but rather of the whole Council of the Elders and Dignitaries (Dumegãwo), in contrary to the untrue allegations of some people. It was a hard Work to build and to maintain permanently such Fortifications over many Kilometers all around the City-State under a high psychological pressure due to possible attacks from the Akwamu warriors. Then these neighbouring warriors were really able to organize raids at any time against their neighbours to rape captives for the booming Slave Trade. Under these hard conditions people did not enjoy their activities on the building site day and night, and there was a risk that the whole project fails. The Monarch Agɔ-Kɔli used therefore to be severe towards lazy and crafty citizens who wanted to live in Security without willing to pay any price for it! Disobeant and defiant citizens were punished therefore severely, NOT through any Death Penalty, as some strange Myths try to propagate it fallaciously over the generations, but rather through the heavy Augmentation of the Work Load! It doesn’t even make any sense, that a Monarch (no matter how wicked he is) should try to eliminate massively his citizens who constitute the Manpower he needs crucially to perform very important Public Works in his own interests at a critical moment!

Many citizens started to understand over the time that the Fortifications called “Agbògbò” that were built all around the City-State of Ŋɔtsie because of a supposed Security Threat from the Akwamu Kingdom is being used by the Monarch Agɔ-Kɔli rather for Mind and Social Control over his Fellows in the city. Then the citizens could notice that the villages and hamlets that were scattered through the whole region from Mount Agu (or Agou in the actual Republic of Togo) to the banks of Lake Volta (also known as Amugã, in the actual Republic of Ghana) were not attacked frequently and constantly by the Akwamu warriors! They could also understand that people living in these villages and hamlets might have surely their own defensive and/or diplomatic Strategies, Means and Resources to face any military and/or political hegemony coming from the Akwamu Kingdom. Another crucial socio-economic aspect related to the life inside the limited space of the City-State of Ŋɔtsie is the rapid demographic Growth of the Population in contrast to limited Soils and Fields that are needed to develop more dynamically the socio-economic activities over the time. These are the objective reasons why many Clans of the Eʋe Speaking People decided to leave the City-State of Ŋɔtsie progressively and in a semi-clandestinity (in small groups), but NOT in form of a “spontaneous and massive Exodus”, as the secular Myths use to tell it over the decades.

T

he «Breakout» of the Eʋe Clans from Ŋɔtsie (Notse), the Foundation of the Eʋe Chiefdoms and the Formation of the «Eʋeland».

- The first negative and surrealist Myth about «Agbògbò» at Ŋɔtsie (Notsie) is that this Wall long of more than 12 Kilometers all around the City, having a thickness of circa 2 meters and a height of circa 2.5 meters as shown by the picture in the previous paragraphs, has been built with Mud and Clay mixed with human Blood (!)

- The second negative and fancy Myth about «Àgbògbò» is that broken bottles and broken glasses have been put in the Mud and Clay by the ‘wicked and tyrannical Monarch‘ (sic!) Agɔ-Kɔli who forced the workers to mix the Mud and Clay barefoot.

- The third fancy Myth about «Agbògbò» is how the whole population could escape one night from these Fortifications in the manner of the hypothetical «exodus» of the Hebrews out of Egypt, because a crevice has been made secretly by all women who have agreed to pour their dirty water at one place on the wall to make it wet and permeable.

But by watching closely the historical context and the geographical configuration in the City-State of Ŋɔtsie from the 17th to the 18th Century A.D., these Myths and Tales can hardly resist to the concrete Facts and to any sane Logic. The Map below illustrates this historical context and the geographical configuration that enable a clear understanding of the so-called “Breakout” of the Eʋe Speaking People out of the City-State Ŋɔtsie:

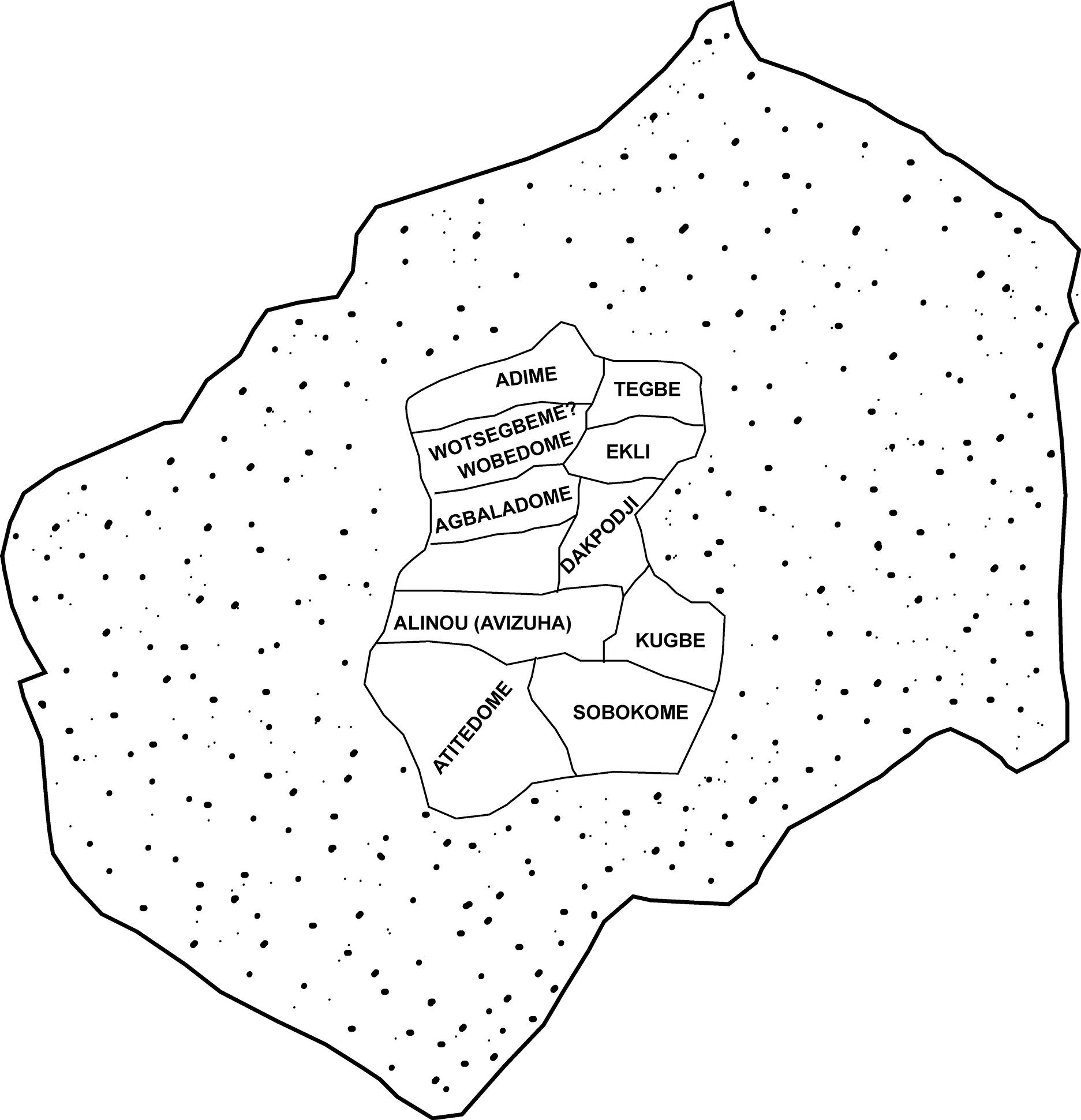

Map showing the different suburbs of Ŋɔtsie (Notse) inside the defensive Fortifications known as Agbogbome. The pointed field all around was private areas for Agriculture, for Livestock, for Hunting and for other economic activities.

(Credits: Angèle D. Aguigah / Nicoué L. Gayibor)

The first objective Remark to be made by watching closely the Thickness of the Wall shown by the picture above and by watching closely its Length (12 Kilometers at least!) all around the City-State concerns the alleged Use of Human Blood to mix the Mud and the Clay during the construction. Any person with a sane Thinking would like to understand how many Millions of Human Beings might have been killed massively at once to get enough Human Blood for such a massive construction! It is clear therefore that the funny story about Human Blood used allegedly during this construction was a silly and dirty Hoax that has been forged many years later with the intention to “demonize” King Agɔ-Kɔli (who was the third or fourth Monarch of the City-State), but also to make naive people believe that their History is full only of bloody and violent episodes. The second objective Remark should be focussed on the allegation about broken bottles and broken glasses mixed with the Mud and the Clay during the construction, with the allegedly ‘malvolent’ intention of the Monarch to torture the workers. The incredible nature of this funny story is demonstrated by the fact that Bottle and Glass were very precious items that were not produced in that part of West Africa at that time, but rather introduced by European traders through the business with wine and liquors. Any person with a sane Thinking would like to know how many tons of Bottle and Glass should be broken and mixed with the Mud during the construction of such a huge Wall! This person should also ask himself or herself how much King Agɔ-Kɔli might have spent to buy from the European traders the required quantity of Glass and Bottle for such a frivolous way to punish disobeant citizens! It is clear in this case also that the story about broken bottles and glasses in the Mud was a silly and dirty Hoax that has been forged many years later with the intention to “demonize” King Agɔ-Kɔli, but also to make naive people believe that their History is full only of bloody and violent episodes. The third Remark concerns the most stupid story about a crevice made allegedly in the thick Wall by pouring collectively and constantly dirty water at a single point. The geographical configuration of the City-State shown by the Map above indicates clearly that the protective Wall was far away from the houses. It is therefore unbelievable that all women used to carry their dirty water over many Kilometers towards this single point! And one should ask also objectively how many years all women in the town have been doing these household chores till a crevice could be drilled in this thick Wall! All these open and objective questions without any objective answer show that the story about an alleged “breakout through a crevice” was also a silly and dirty Hoax that has been forged many years later. If other stories account that the Akposso People living in the hills and mountains in the North-West of the City-State could also find refuge inside the Fortifications during crisis times, it is clear that the Inhabitants of Ŋɔtsie as well as outsiders who had trusted contacts with the City-State could move in and move out without any great problem. In respect to all these objective historical Facts, any person having a sane Thinking should ask today why the gradual departure of some Eʋe Clans to settle down outside of Ŋɔtsie has been presented later as a «Breakout» (sic!) and as an «Exodus» (sic!) of a whole Community fleeing away from an allegeldy tyrannical Monarch. The answer to this question is to be found in the political Struggles and in the ideological Intentions at that time. At the political level, the collapse of the Kingdom of Tado since the end of the 16thCentury A.D. had opened the way to the emerging of new Kingdoms as offshoots. The first offshoot was in the East and was the Kingdom of Allada that evolved later to the foundation of the Kingdom of Dahome (or Agbome) by the beginning of the 17th Century A.D.. This situation had empowered the Elders and Dignitaries of Ŋɔtsie to make of their modest Town a powerful City-State that could also evolve gradually to a Kingdom able to play a major political role in the region beside the Kingdom of Dahome. Such a political hidden agenda of the Elders and Dignitaries for an expansion was stopped later in the West by the immigration of the Akwuamu people by the begining of the 17th Century A.D. towards the banks of Lake Volta ( or Amugã ) where they founded their Kingdom beside the different Eʋe-Chiefdoms that emerged after the progressive departure of many Clans from Ŋɔtsie. By claiming that the City-State of Ŋɔtsie was the common Capital from where all Eʋe-Clans escaped under difficult circumstances (even though it is not historically true!), the newly founded Eʋe-Chiefdoms just wanted to define themselves as a homogeneous Political Entity face to the Dahome Hegemony in the East and face to the Akwuamu Hegemony in the West. The success of this political strategy of Unity is illustrated by the bright Military Victories of the Coalitions of the modest Eʋe Militia Armies (Aʋakalɛnwo in Eʋegbe) over the very strong Asante Armies and over the very strong Dahome Armies during the 18th and the 19th Centuries A.D. At the ideological level, the mythical «Exodus» of the Eʋe Speaking People out of Ŋɔtsie seems to pursuit the simple goal of Self-Legitimation, of Self-Esteem and of Self-Glorification. The main idea behind this Self-Legitimation, behind this Self-Esteem and behind this Self-Glorification is that the Eʋe Speaking People that are structured through their local Chiefdoms must be considered globally as an autonomous, free and pragmatic political Entity beside the famous Kingdom of Dahome, beside the famous Kingdom of Akwamu and beside the powerful Kingdom of Asante, even though their previous Dream to set up also a famous and powerful Kingdom in Ŋɔtsie could not be fullfiled completely. The early linguistic, historiographic and litterary Works done by the first European missionars and their African followers and helpers since the beginning of the 19th Century A.D. (see for example Schlegel 1857 & 1906, Henrici 1891, Knüsli 1892 and Reindorf 1895 cited in the References) have absorbed these Myths without any deep and objective Investigation and without any systematic Reconstruction of the historical Facts from the perspective of the concerned people. These Works have even tried to stylize and adapt the Myths of the Eʋe Speaking People to the biblical myths about the Hebrews such as the funny story of the 40-years-“Exodus” out of Egypt, so that they appeared later as the “standard and official History” of the Eʋe Speaking People. Of course, these Myths have helped people over generations to be proud somehow of their cultural and linguistic Identity that goes beyond geographical and political boundaries. A concrete illustration of the constructive aspect of these Myths is the bi-annual celebration of the Festivities of «Agbogbozã» that bring Representatives of all the Eʋe Speaking People together, no matter which Citizenship, which political Opinion or which religious color they have. But it is necessary today to go beyond these Myths in order to restore objectively the Historical Truths in the interest of the forthcoming generations. Then a social group or a Community that had lost its True History is no more able to understand in the present some concrete Facts, some significant Events and some decisive Orientations for a better Future with new Challenges. That is why the Motto of the Eʋe Speaking People still remains the following:

| Dates (Estim. & Dates) | Migrations/Historical Events (Given Dates are Estimations and precise Dates in some cases.) |

|

|---|---|---|

| From ca. 900 A.D. to 1000 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1200 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1250 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1300 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1450 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1500 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1600 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1680 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1700 A.D. |

|

|

| ca. 1720 A.D. |

|

|

| From ca. 1750 A.D. to 1860 A.D. |

|

|

| From 1869 A.D. to 1875 A.D. |

|

|

| 5 th July 1884 |

|

|

| August 1914 A.D. |

|

|

| Since 1945 A.D. |

|

© K. Kofi FOLIKPO, PYRAMID OF YEƲE, 2002 – 2020, All Rights reserved.

- (Fio) Agbanon II: Histoire de Petit-Popo et du royaume Guin. Lome: éditions Haho/Paris: éditions Karthala, 1991. Series:Les chroniques anciennes du Togo, No. 2 (First publication: 1934).

- Agbodeka, Francis: A handbook of Eweland. Vol. I: The Ewes of Southeastern of Ghana. Accra: Woeli Publishing Services, 1997.

- Amenumey, D.E.K.: The Ewe in Pre-Colonial Times. A Political History with Special Emphasis on the Anlo, Ge and Krepi. Accra: Sedco Publishing, 1986.

- Avogbedor Daniel: The Transmission, Preservation and Conservation of Song Texts: A Psycho-Musical Approach. In: Cross Rhythm: Occasional Papers in African Folklore, No.2, pp. 67-97: , 1985.

- Brosses (De), Charles: Du culte des dieux fétiches, ou parallèle de l’ancienne religion de l’Egypte avec la religion actuelle de la Nigritie. Paris, 1760. (new edition by Gregg in 1972 in Farnborough).

- Budges, Wallis E.A.: An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary. with an index of English words, king list and geographical list with index, list of hieroglyphic characters, coptic and semitic alphabets, etc. Vol. I & II. New York: Frederick Ungar publishing Co.

- Capo, Hounkpati B.C.: Renaissance du Gbe. Réflexions critiques et constructives sur EVE, le FON, le GEN, l’AJA, le GUN, etc … Hamburg:Buske, 1988.

- Capo, Hounkpati B.C.: A Comparative Phonology of Gbe. Berlin: Foris Publications, 1991.

- Cornevin, Robert: Histoire du Togo. 4e édition. Paris: Levraut, 1969.

- Cornevin, Marianne: Les secrets du continent noir révélés par l’Archéologie. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 1998.

- Datey-Kumordzie, Samuel: Yeweh- oder Hu-Religion: Der Sogbo-Musikkult. (Thèse de Doctorat, Universität Köln, 1989)

- Davidson, Basil: A History of West Africa: 1000 -1800. (The Growth of African Civilisation). New revised edition, 2nd impression. London: Longman, 1977.

- Davidson, Basil: Modern Africa: A Social and Political History. 3rdEdition. London: Longman, 1994.

- Davidson, Basil: West Africa Before the Colonial Era: A History to 1850. stEdition. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Deller, Karlheinz: Tamkaru-Kredite in neuassyrischer Zeit. In:Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 30, N° 3, pages 233 – 254.

- Dickson, Kwamina B.: A Historical Geography of Ghana. Cambridge: Cambridge Universits Press, 1969.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta: Nations Nègres et Culture. 4e édition. Paris: Présence Africaine, 1979.

- Dohnani, Yawo D. A.: L’Ewe ou la Langue des Pyramides. University of California: University of California Press, 1988.

- Effa-Gyamfi, Kwaku: Traditional History of the Bono State. Legon: Institute of African Studies, 1979.

- Effa-Gyamfi, Kwaku: Archeology and the Study of early African Towns: the West African Case, especially Ghana. In: West African Journal of Archeology, N° 17, 1987, pages 229-241.

- Erman, Adolf & Grapow, Hermann: Ägyptisches Handwörterbuch. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1921.

- Erman, Adolf & Grapow, Hermann: Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache. Im Auftrage der deutschen Akademien. Zweiter band, erstes Heft. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs Verlag, 1937.

- Folikpo, Kofi Komdedzi: Emprunt linguistique et univers ontologique trans-culturel: Le cas de l’apport du Gbè au hébreux calssique et à la Kabbale hébraïque. (Paper published in 2007 on www.togocity.com and to be downloaded under the link Academia.edu.)

- Folikpo, Kofi Komdedzi: Analyse sémantique Ethnonymes, des Patronymes, des Toponymes et des Hydronymes. Published in 2017 at Presses Académiques Francophones (PAF), (Manuscript can be downloaded at Academia.edu)

- Frobenius, Leo: Atlantis. Volksmärchen und Volksdichtungen Afrikas. Die Atlantische Götterlehre. Jena: Eugen Dierderichs Verlag, 1926.

- Frobenius, Leo: Kulturgeschichte Afrikas. Prolegomena zu einer historischen Gestaltlehre. Wuppertal: Peter Hammer Verlag, 1993 (published formerlly in 1954 in zurich by Phaidon).

- Froehlich, Jean-Claude: Les montagnards “paléonigritiques”. Paris: Editions Berger-Levrault (ORSTOM-IRD), 1968.

- Gaba, Christian: Scriptures of African People: Ritual Utterances of the Anlo. New York: Nok Publishers, 1973.

- Henrici, Ernst: Lehrbuch der Ephe-Sprache. Anlo- Anecho- und Dahome-Mundart. Lindau: Verlag Unikum, 2013 (First Publication in 1891).

- Ige, Akin & Rehren, Tilo: Black sand and iron stone: iron smelting on Modakeke, Ife, South Western Nigeria. In: iams, N° 23, pages 15-20, 2003. Can be downloaded from this link on Academia.edu.

- Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: Die Geschichte Schwarzafrikas. Frankfurt/M: Fischer Verlag, 1981.

- Knüsli, Annna: Wörterbuch Deutsch-Ewe. Bremen: Norddeutsche Mission, 1892.

- Kossi, Komi E.: La structure socio-politique et son articulation avec la pensée religieuse chez les Aja-Tado du Sud-Est Togo. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990.

- Kubik, Gerhard: Theory of African Music. Vol. 1. Wilhelmshaven: Florian Noetzel Verlag, 1994.

- Lafage, Suzanne: Français écrit et parlé en pays Ewé (Sud-Togo). Paris: Selaf, 1985.

- Lange, Dierk(a): Origin of the Yoruba and “the Lost Tribes of Israel”. In: Anthropos, Band 106, Nr. 2, pages 579 – 595, 2011.

- Lange, Dierk(b): The Founding of Kanem by Assyrian Refugees ca. 600 BC: Documentary, Linguistic and Archeological Evidence. Boston: Working Papers in African Studies, N° 267, 2011.

- Lange, Dierk(c): Abwanderung der assyrischen tamkaru nach Nubien, Darfour und ins Tschadseegebiet. In: Bronislaw Nowak et al. (eds.), Europejczycy Afrykanie Inni: Studia ofiarowane Profesorowi Michalowi Tymowskiemu, pages 199-266, Warzawa: 2011.

- Lara Peinado, Frederico/Cabrero Piquero, Javier/Cordente Vaquero, Félix/Pino Cano, Juan Antonio: Diccionario de instituciones de la Antigüedad (1a edición). Fuenlabrada (Madrid): Ediciones Cátedra (Grupo Anaya, Sociedad Anónima), 2009.

- (De) Medeiros, François: Peuples du Golfe du Bénin. Paris: Khartala, 1984.

- Métraux, Alfred: Voodoo in Haiti. Gifkendorf: Merlin Verlag, 1996. (orginal title: Le Vaudou haitien. Paris:Gaillimard, 1959)

- Obenga, Théophile: Les origines africaines des Pharaons. In: Afrique Histoire. Magazine trimestriel de l’histoire africaine , No. 7, 1983, pages 47 – 48.

- Obenga, Théophile: L’Egypte pharaonique tutrice de la Grêce de Thalès à Aristote. In: Ethiopiques . No. 1-2, Vol. VI, 1er semestre 1989, pages 11 – 45.

- Obenga, théophile: Origine commune de l’Egyptien ancien, du copte et des langues négro-africaines modernes. Introduction à la linguistique historique africaine. Paris: l’Harmattan, 1993.

- Pazzi, Roberto: Introduction à l’histoire de l’aire culturelle ajatado. Lomé:INSE/UB, 1979.

- Randsborg, Klavs et al.:Subterranean Structures. Archeology in Benin. In: Acta Archeologica, vol. 69, 1998, pages 209-227.

- Randsborg, Klavs: Projet benino-danois d’archéologie (BDArch). Report on the Field Campaign 2004. Copenhagen: Center of World Archeology, 2005.

- Reindorf, Carl Christian: The history of Gold Coast and Asante, based on traditions and historical facts of a period comprising more than three centuries from about 1500 to 1860. London: Kegan Paul/Basel: Basel Mission, 1895.

- Reisner, George Andrew: Excavations at Kerma I-III/IV. In: Harvard African Studies Volume V. Ppeabody Museum of Harvard University. Cambridg Massachussetts, 1923.

- Schlegel, Bernhard Johannes: Schlüssel der Ewe-Sprache. Dargeboten in den grammatischen Grundzügen des Anlo Dialekts derselben, mit Wörtersammlung nebst einer Sammlung von Sprüchwörtern und einigen Fabeln der Eingeborenen. Bremen: Verlag Valett, 1857.

- Schlegel, Bernhard Johannes: Beitrag zur Geschichte, Welt- und Religionsanschauung des Westafrikaners, namentlich des Eweers. In: Monatsblatt der norddeutschen Missionsgesellschaft, 1906, pp. 406-408.

- Spieth, Jakob: Die Ewe-Stämme. Material zur Kunde des Ewe-Volkes. Berlin: Reimer Verlag, 1906.

- Spieth, Jakob: Die Religion der Eweer in Süd-Togo. Berlin: Dietrich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1911

- (De) Surgy, Albert: La partition des unités cycliques du temps en pays Evhe (Togo et Ghana). In: Journal de la Société des Africanistes, tome 45, fascicule 1-2, pages 37-67, 1975.

- (De) Surgy, Albert: Le culte d’Afa chez les Evhé du Sud-Togo. Paris: Editions Orientalistes de France, 1981.

- (De) Surgy, Albert: Le système religieux des Evhé. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1988.

- Traunecker, Claude: Les dieux d’Egypte. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996 (Collection Que-sais-je?).

- Verger, Pierre: Flux et reflux de la traite des nègres entre le Golfe de Bénin et Bahia do Todos os Santos du dix-septième au dix-neuvième siècle. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1968.

- Verger, Pierre Fatumbi: Ewé. The Use of Plants in the Yoruba Society. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 1996.

- Wachsmann, Klaus P.: Human Migration and African Harps. In: Journal of the International Folk Music Council, Nr. 16, page 84-88, 1964.

- Welsby, Derek A.: The Kingdom of Kush. The Napatan and Meroitic Empires. London: British Museum Press, 1996.

- Wilks, Ivor: Asante in the nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

- Wilks, Ivor: Akwamu 1640 1750: A Study of the Rise and Fall of a West African Empire. Trondheim: Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of History, 2001.

- Westermmann, Diedrich: Wörterbuch der Ewe-Sprache. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1954.